Another key to the making and enjoyment of a good poem is the

element of tone. The concept of tone

is somewhat difficult to define but it can be thought of as the attitude of the

poet (or the speaker of the poem) toward the poem or its subject matter- even

toward the audience of the poem. The tone of the poem can carry loads of hidden

meaning (remember your mother saying to you, I don’t like the tone of your voice?) or can itself be what the

poem is ‘about.’ The tone can be laid out or amplified by the language the poet

uses, the imagery, the meter, and the diction.

One of my favorite examples of how effectively tone can be

used to carry the weight of a poem is Robert Hayden’s Those Winter Sundays: (to hear Robert Hayden movingly read this poem,

click here.)

Sundays too my father

got up early

and put his clothes on

in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked

hands that ached

from labor in the

weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No

one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the

cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would

rise and dress,

fearing the chronic

angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently

to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good

shoes as well.

What did I know, what

did I know

This is a poem of reticence, a cold, angry place but what

makes it so memorable is that it is also a place of reverence for the poet’s

father and regret for the poet’s self-centeredness and lack of insight. The

first stanza is full of hard consonant sounds (especially ‘k’ : blueblack cold,

cracked hands that ached, banked fires) that sets the reader down in a cold, angry,

relentlessly blue-collar place that slowly begins to warm in both temperature

and language though the father, whose simple yet profound actions on behalf of

the poet elevate him to a lofty position, remains largely unreachable. One can

almost feel Hayden’s aching remorse in those last two lines, the repetition of

the first half of his question emphasizing the obvious, unspoken answer.

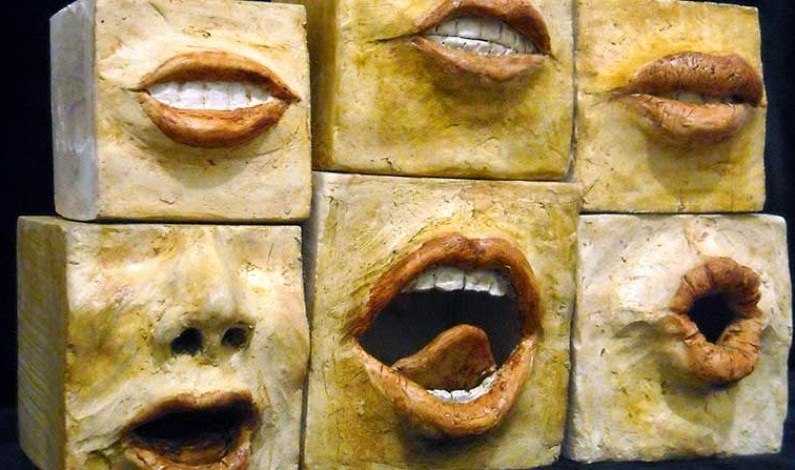

Another favorite is Jack

Gilbert’s Michiko Dead which

details how the poet has dealt with the death of his wife. It’s tone is

amazingly devoid of any hint of sorrow but is quite matter-of-factual about how

one deals with tremendous grief. It is that very understated, detail-laden tone

that gives the poem its lasting power (Notice too how the appearance of the

poem on the page mimics the very box he describes carrying!):

He manages like

somebody carrying a box

that is too heavy,

first with his arms

underneath. When their

strength gives out,

he moves the hands

forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling

the weight against

his chest. He moves

his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin

to tire, and it makes

different muscles take

over. Afterward,

he carries it on his

shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm

that is stretched up

to steady the box and

the arm goes numb. But now

the man can hold

underneath again, so that

he can go on without

ever putting the box down.

Tone does not need to be one-dimensional. It can also shift,

sometimes abruptly, which can add to the enjoyment of the poem. A good example

of this is in Richard Wilbur’s A Barred Owl:

The warping night air

having brought the boom

Of an owl’s voice into

her darkened room,

We tell the wakened

child that all she heard

Was an odd question

from a forest bird,

Asking of us, if

rightly listened to,

“Who cooks for you?”

and then “Who cooks for you?”

Words, which can make

our terrors bravely clear,

Can also thus

domesticate a fear,

And send a small child

back to sleep at night

Not listening for the

sound of stealthy flight

Or dreaming of some

small thing in a claw

Borne up to some dark

branch and eaten raw.

The

first stanza delightfully describes the calming of a small child who has been

frightened by the sound of an owl. It is very domestic and calming in its tone

but this tone abruptly shifts in the poem’s second stanza wherein the poet

revisits the gruesome truth behind the parent’s/poet’s soothing words. The

abruptness of the change lends a sinister air to the obscuring power of words.

The

tone of a poem is an element of the poem’s presentation that can often be felt

viscerally and requires no special degree in Poetics and Prosody to appreciate.

Try reading the next poem you read (and I hope that it will be soon) with a

little less trepidation, secure in the knowledge that by listening and feeling

for the poem’s tone, you are ‘getting’ a good deal of what the poem is likely

‘about.’

No comments:

Post a Comment